In the time of Covid-19 and the eruption of the festering wound of racism in this country, I find myself pondering mortality and the importance of acting in values-congruent ways more than usual.

The deaths of Ruth Bader Ginsberg (1933-2020) and Breonna Taylor (1993-2020) have both dramatically changed the landscape in which we live. An 87-year old, white, Jewish, legal scholar, and U.S. Supreme Court Justice, Ginsberg fought for women’s rights and the rights of those on the margins for decades. Her legacy can be seen across law books, films, and in the structural DNA of policy in the United States. Taylor, a 26-year old Black woman studying to be a nurse, was gunned down in her own home in March just a few days before the nation locked down in a pandemic. Their lives and deaths could hardly have been more different, and their narratives have further mobilized thousands. Certainly, RBG’s passing is a singular event which has thrown our political system from a free fall into a tailspin while Taylor’s death represents yet another death of an unarmed Black person at the hands of the police.

It’s important to emphasize that Breonna and Ruth were real people with real lives and many people for whom their deaths leave deep, personal grief. What I am writing about here is more abstract. The deaths of Taylor and Ginsberg intersect in 2020 as events which demand action and signify a wounded world. Ginsberg who passed comfortably, surrounded by family, is remembered as a ‘tzadik,’ a true righteous person in the Jewish tradition, was the first woman and the first Jewish person to lie in State at the United States capitol. Breonna Taylor was not a household name until March, 2020, and it was only in death that she became “newsworthy.” The nature of Breonna Taylor’s last minutes has fueled my nightmares and actions for months. Ginsberg’s death represents an extant threat to myriad freedoms, primarily to women and those of us on the edges.

For too long, psychologists and allied mental health professionals have been encouraged to remain neutral in our public-facing lives lest we create some kind of rift in our relationships to clients. In this neutral stance, we have created and maintained chasms between access to mental health care and the people who need it most. White, cisgender, heteronorming, Judeo-Christian men have dominated the narrative of psychology while shunting off Black and Brown women and queer folks to the so-called “lesser” fields of social work, nursing, and counseling. As any systems psychologist will tell you, a system, once established, will work to sustain itself and maintain homeostasis. In our system, neutrality works for those in power because it minimizes rage and invalidates social action. Old-school psychology would argue that if you struggle under systems of oppression, that isn’t something to bring into session. Sure, some argue, the environment you exist in may be rough, but that is not something to examine in therapy because it can’t be changed at an individual level. A psychologist’s job is not to shift anything beyond an individual’s thoughts, feelings, or actions; thus, a psychologist must not be seen to have any stake in the world writ large. This works for those who benefit from social inequity, for Freud’s “worried well,” and for mental health practitioners who believe our work begins and ends at the office door. However, it has deprived communities and policy makers our perspective, placed unnecessary burdens on those very professionals shunted off, created distressing personal-professional divides, and most importantly, left so many people on the edges feeling unseen and literally untreated.

Returning to Taylor and Ginsberg, what strikes me most about the passing of these two remarkable women is not their differences; rather, it is how the fragility of life stands as a call to action. We have been witness to a dramatic shift in the cultural narrative around human rights and social justice. Here in the United States, we find ourselves at a critical moment and many of us are feeling the galvanizing power of communities coming together to speak truth to power. I don’t pretend to think that everyone reading this will immediately go out and protest or engage in overt social justice action. What I do hope is that each of us will find a way to connect our personal values and professional lives in profound ways. By acknowledging inequity, engaging in learning, and acting with integrity, we can make profound change. We spend decades dedicated to understanding human behavior and bringing healing wherever we can, why not allow ourselves to use all this experience and knowledge to better ourselves, our clients, and our world?

Whit Ryan 2020

Last week several momentous things happened in my life. In no particular order, I accepted an offer of admission at the

Last week several momentous things happened in my life. In no particular order, I accepted an offer of admission at the

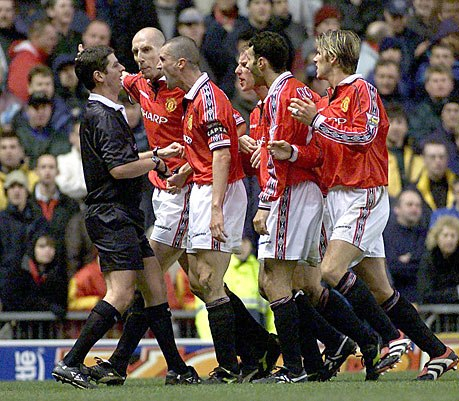

uld anyone want to be an umpire?” I hear this question a lot in my roles as both a sport and performance consultant and as an umpire. When someone asks that, what they are really saying is: why do you want to put yourself in the line of fire? What possible motivation do you have to be yelled at, questioned, berated, belittled, scrutinized, evaluated, rated, and basically run through the wringer on a game-to-game basis? There are as many reasons as there are people who choose to be on the other side of the whistle, behind home plate, or in the big chair court-side. For many it is a passion for the game, an aptitude for applying the rules, a desire to give back to their sport, a motivator for ongoing physical fitness, and the thrill of the challenge. Each official has their own reasons and many of us will gladly talk about why we love it. But the question stems from the same source as the sign reminding spectators that umpires and coaches are humans. Being a sports official at any level can be a challenge. I’ll touch on a few of those challenges and then propose a few ways SPP consultants may be able to help officials cope with them.

uld anyone want to be an umpire?” I hear this question a lot in my roles as both a sport and performance consultant and as an umpire. When someone asks that, what they are really saying is: why do you want to put yourself in the line of fire? What possible motivation do you have to be yelled at, questioned, berated, belittled, scrutinized, evaluated, rated, and basically run through the wringer on a game-to-game basis? There are as many reasons as there are people who choose to be on the other side of the whistle, behind home plate, or in the big chair court-side. For many it is a passion for the game, an aptitude for applying the rules, a desire to give back to their sport, a motivator for ongoing physical fitness, and the thrill of the challenge. Each official has their own reasons and many of us will gladly talk about why we love it. But the question stems from the same source as the sign reminding spectators that umpires and coaches are humans. Being a sports official at any level can be a challenge. I’ll touch on a few of those challenges and then propose a few ways SPP consultants may be able to help officials cope with them.

before and you didn’t think it was for you, I have a question. Did you try it once and think it was lame or too hard? Did you have an image of sitting in a full lotus position with birds perched on your shoulder and did you get frustrated when all you could think about was how much your nose itched and how the sweat was working its way toward your butt? You are NOT alone! Were you confused, bored, or distracted? That is TOTALLY NORMAL.

before and you didn’t think it was for you, I have a question. Did you try it once and think it was lame or too hard? Did you have an image of sitting in a full lotus position with birds perched on your shoulder and did you get frustrated when all you could think about was how much your nose itched and how the sweat was working its way toward your butt? You are NOT alone! Were you confused, bored, or distracted? That is TOTALLY NORMAL.